This is the full paper I gave at the From Paper to Pixels; Transmedial Traffic in Architecture Drawing at the Jaap Bakema Study Centre, TU Delft in association with The New Institute, Rotterdam. It's useful in laying out some of my thoughts about rendering as a potential practice for radical imagination. This is the full 3,700 words including the abstract, I've included some of the slides but not all of them. My apologies.

Abstract

Architectural renders form the cornerstone of public communication in contemporary architecture. New developments are reported and promoted to the public using highly stylised glamorous and romantic renders that conform to the dominant societal values and politics: aspiration, wealth, executive and family lifestyles, urbanism. This consequently results in an homogenous aesthetic. Rendering software and its application works as a self-reciprocating aesthetic style of tropes that reinforce these dominant politics and values. Images of the future reinforce the way that future is developed [Bassett et al. 2013] and so in creating these renders, developers and architects build a narrow and linear vision of the future in line with the values they espouse. In tun, the software is further developed to reinforce these tropes. [Plummer Fernandez 2014]

Because of their dominance, projects of resistance cite these renders as targets. Campaigns attempting to halt redevelopment, gentrification or expensive public-private projects hold up these renders as leitmotif effigy, symbols of the top-down power the renders represent.

However, the growing accessibility and usability of rendering software presents an alternative space for political action. Rather than simply becoming sites of resistance, rendering software has the potential to be a site of radical, critical imagination. As Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams point out in their book ‘Inventing the Future’ - We ‘can’t resist new worlds into being’ [Srnicek & Williams 2015] but we can begin to render new worlds as alternative visions that wildly challenge the dominant hegemony of rendered futures.

Activists and artists have begun to use rendering software as a tool for creating new imaginaries and feeling critical debate about the shaping of the future. Their projects challenge histories, the laws of physics and create sprawling meta-fictions that exceed the abilities of other media. At the same time these projects make tongue-in cheek attacks at the narratives and aesthetics of architectural rendering and dominant power structures.

This paper lays out a brief analysis of the relationship between future imaginaries and the dominant aesthetics of contemporary rendering software and suggests that this software presents a space for developing political imaginaries that can lead change and critical discussion. It uses examples and case studies from theorists and artists working in the space of 3D rendering to lay out a framework for where these kinds of practices might start to exist and act and suggests tactics and techniques for a new radical culture of rendering.

Introduction

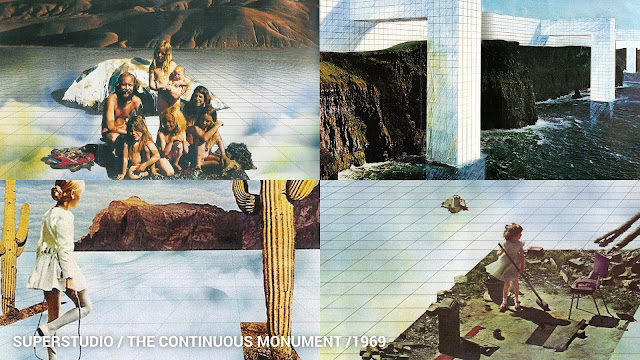

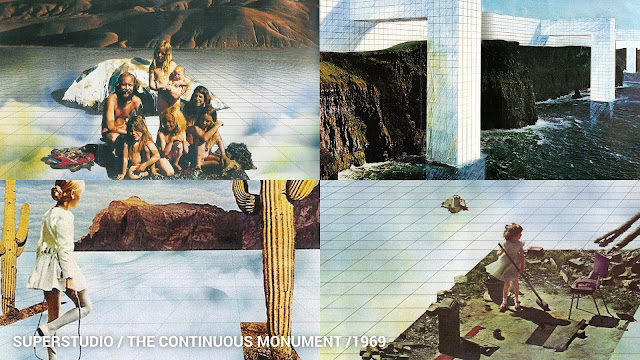

Speaking at London’s Architecture Association in 1971, Adolfo Natalini, founder of the radical architecture firm Superstudio presented an argument for Superstudio’s withdrawal from the work of architecture - producing buildings.

The self-appointed role of Superstudio as an architecture firm remains contentious since not a single one of their instantly recognisable designs was ever built. There are compelling arguments [Elfline, 2016] that the work that Superstudio pursued sat within the context of the leftist politics of the time and that they, like other critical practitioners both contemporary and historical, created obstructions to encourage disruption and engagement rather than buildings that continued the neoliberal hegemony they despised. Whether they created or obstructed, Superstudio recognised that the work of architecture is no more in construction than music is in getting to the end of a song. The work of architecture, design, art and all those fields with the privilege of creativity and critique is in building future imaginaries - renders of the way the world might be, orientating visions of future material products that ‘enchant’ our future.

In this way, architecture uses drawings, plans and increasingly, renders to materialise the future and present it to their audience. People relate to the built world first through its rendering before its construction. In 2015, when controversy surrounded the funding and construction of

Thomas Heatherwick’s Garden Bridge in London, it had yet to exist. The future imaginary used was one of two or three renders of the bridge. It became the object around which public debate formed [Di Salvo, 2009] despite being, culturally at least, entirely imaginary.

Human material culture is riddled with future imaginaries. Cinema perhaps leads this field and several studies have pointed out how the penetration and resolution of these imaginaries feeds back into reality [Bassett et al. 2013]. Stephen Spielberg’s 2001 film,

Minority Report is a particularly pertinent example. The fictional and completely rendered gestural interface used by Tom Cruise has held sway over 15 years of interface development and technology headlines. As rendering becomes a faster and more affordable alternative to expensive sets and protracted film shoots, television and advertising are following suit. Almost all car adverts in print and moving image are rendered, in 2014, 75% of

IKEA catalogue images were 3D renders [Parkin, 2014]. The benefits of this approach are obvious, rendering is cheap, affordable, quickly iterative and allows of circumventing external factors: For example, the troublesome laws of physics. In 3D-rendering, dramatic sunrises can be made to last forever over perfect and empty mountain roads.

The danger is that we are limiting our imagination by creating a homogenous rendered visual culture. Buildings on development hoardings begin to look identical, cars and sofas have the same haptics. The developing visual language of 3D rendering is becoming self-reinforcing in its aspirations. We run the risk of a visual

Shazam effect for rendered images.[Thompson, 2014] The

Shazam effect, named for the music recognition software, is a phenomena whereby record companies produce music based on the download habits of users thus creating a reinforcing cycle of all music sounding the same. Rendering software developers increasingly develop tools and processes of their software around the demands of some of their biggest clients - architects and advertisers - creating a self-reinforcing aesthetic loop. The 3D digital artist Matthew Plummer-Fernandez claimed once in an interview to be able to recognise the software used to render buildings based on the ‘off-the shelf’ algorithms and plugins [Plummer-Fernandez, 2014].

A very real example of the Shazam effect in play is the work of

Crystal CG, a Beijing-based rendering company who offer ‘fast turnaround, high quality and inspiring presentations, including 3D renderings, animations, multimedia and virtual reality.’ The website is packed with identikit steel and glass structures brooding under dramatic sunsets with the requisite amount of shadow-people render ghosts and street greenery to make an appealing frontispiece to any development hoarding. Their partners and clients are almost every major developer, several Olympic development projects and a range of ultra-rich micro-nations. The chances are you’ve seen some of their work and if not one of Crystal CG’s renderings then one of their competitors’.

The visual language epitomised by Crystal CG is thoroughly embedded in visual culture, at least in richer parts of the world. These developments could be anywhere, they are after all produced by artists who have never visited the sites in question and probably know very little of the local culture. They simply materialise a set of plans into something visually appealing and striking. However, the sheer onslaught of this aesthetic is becoming the steering narrative for what the future should be. In a recent trip to Colombo, Sri Lanka, I had a conversation with a representative of a redevelopment group building a massive office and shopping complex in the heart of the city. When I pointed out that the building looked like it could be from anywhere and asked who had created the render he said that he didn’t know… ‘some Chinese company.’

Looking at the rendered city sets of sci-fi films like

Elysium and

Star Wars reveals an aesthetic continuum between the hyper-real development renderings that pervade the city and how we imagine the future city to be. The rise of white and gleaming tower i inevitable as is the kitsch homage to the 70s utopian visions of space life. As if to concretise this relationship between urbanists, rendering artists and games developers, a 2014 project between city-developers and game-developers created rendered imaginaries of how Britain might look in the 22nd century showing cities like Manchester as hyper-real assemblages of placeless architecture and fantasy technology [Clarkson, 2014].

The future is imagined through these visual artefacts, and as they become more and more identical we run the significant risk of reducing our range of imagination. We might end up building an aesthetic cage in which we find it impossible to imagine a future beyond the gleaming towers and rendered greenery, in which the 45-degree skyline view becomes all encompassing and we dream of endless sunsets over our glass balconies.

In the late 1960’s Superstudio cannily seized on the cultural penetration that visual culture allows to seed alternative future imaginaries to what they saw as a visual hegemony. Their projects were visually rich and dizzying, playing into the language of cinema, collage and colour photography to inject a counter-narrative into popular culture. They realised, through exhibition and publication the reach of their work and how to play with these tools to introduce new ideas and critique. With the prevalence of rendering tools in contemporary culture, we can start to draw parallels with other contemporary practices and see how artists are using the tools of luxury flat renderings to build alternatives or critique the aesthetic hegemony we have.

The English word ‘render’ finds its etymology in the Latin ‘reddere’ - to ‘give back’ from which we also get the English word ‘redeem.’ So, in the spirit of redeeming myself I want to suggest an exceptionally loose categorisation of radical approaches to rendering largely from outside the architecture world:

Un-Rendering,

Low-Rendering and

Hyper-Rendering. These categories are structured by the tactics that practices used to achieve the objective of engaging audiences in critical debate. In Un-Rendering we find practices trying to undo the render, to uncover the underlying technical reality of the rendering produced. Low-Rendering practices use intentionally low-resolutions, simplified, distorted and ambiguous imagery to encourage audiences to critically imagine the wider context of the work or the specifics of its functioning. And in Hyper-Rendering practitioners push the technical boundaries of rendering software and materials to create radical aesthetic imaginaries that critique the homogeneity of the rendered landscape. These practice create

Overton-Window effects, introducing extreme and radical ideas in order to try and stretch the standard deviation of styles. I’ve also referred almost exclusively to practices outside what could be considered architecture. These practices are artists seizing the tools of architects to do other things, to think and act in non-architectural ways.

Un-Rendering

Underlying any rendering we find a host of systemic conditions and requirements; the intermeshed complexities of planning, logistics, legal restrictions, engineering and infrastructure. The rendered image normally used for public consumption is the sharp end of this long and expensive sword. Practices of unrendering seek to investigate and reveal what is behind the rendering, to trace the thread of reality that the fantasy render is tied to.

Crystal Bennes’ archiving project

#developmentaesthetics aims to ‘chronicle the rise and rise of the inane language and visuals used to market new buildings and developments in London (and increasingly across the UK).’ [Bennes, 2013] By presenting photographed images on a blog with almost no commentary, she flattens them and removes them from the context of glamour and aspiration in which they are supposed to be contextualised. By presenting them together she encourages us to draw comparisons between the aesthetics and language of contemporary architecture and development and critique the hegemony of the renders and hyperbole that surrounds them. Dan Hill’s similarly archival ongoing project

Noticing Planning Notices serves to draw attention to the role of planning notices in civic engagement with development. He makes the point that ‘…the primary interface between the UK’s planning system and the people and places it serves is a piece of A4 paper tied to a lamppost in the rain.’ Rather than renderings serving as the main means of public engagement with the future of their cities, he extols a better understanding of planning processes as the ‘dark matter’ of future city development.

More radically, the artist Hito Steyerl, in her 2013 video work,

How Not to be Seen: A Fucking Didactic Educational .MOV File highlights some of the technical limitations of rendering software. She tells us that ‘to become invisible, one has to become smaller or equal to one pixel.’ By playing to the aesthetic of pixel orientation markers, green-screening, rendering and satellite photography, she suggests ways that we might uses chromakeying and other technical processes to subvert the rendered and computer visible world and challenge renders on their own terms - unrendering ourselves. She also offers her own critique of rendered future imaginaries, citing the gated and exclusive communities of developers and describing how they enable invisibility and un-rendering for the ultra-rich at the other end of the spectrum.

Low-Rendering

Low-rendering intentionally challenges the spectacle of the hyper-real. Rather than presenting complete worlds of smiling residents, playing and working in a perfectly lit and maintained space, low-renders show only a framework or an idea and invite the audience to sketch out the details, often drawing their own conclusions as to the purpose and function of the plan.

In Dunne and Raby’s 2013 project,

United MicroKingdoms, the UK has been split into four allegorical political and economic systems: Digtiarians, a society governed by algorithms with a mobile-phone tariff style economy; Communo-Nuclearists, a zero-sum communitarian economy based on the near limitless energy supplied by nuclear power; Bio-Liberals, a techno-utopia social democracy based on synthetic biological technology and Anarcho-Evolutionists, an anarchist society based on self-augmentation and experimentation. Rather than represent these speculative societies through complex RAND-style diagrams, masterplans and papers, the designers created vehicles used by the citizens; driverless robocars for the Digitarians, a nuclear-powered train disguised as landscape for the Communo-Nuclearists, slow biological machine cars for the Bio-Liberals and a communal bicycle for the Anarcho-Evolutionists.

The aesthetics of the vehicles presented are themselves low-resolution, with simplistic designs and pastel colours. They’re not meant to reflect the technical demands or limitations of the technologies but the wider contextual system of politics in which they’re embedded. Similar in detail and sheen to how the background of architecture renderings often appear, (non-descript grey or white blocks fading into the software’s clipping distance.) the models and images of

United MicroKingdoms serve as tools for thought and boundary marking rather than outcomes in their own right.

In Superflux’s 2015 film

Uninvited Guests, a similar tactic is used. Ostensibly a design fiction about a ‘smart’ future, the film’s technological devices - a walking stick, a fork and a bed - all variously connected to the Internet and sharing data are intentionally shown in low-resolution as generic fluorescent yellow objects with no detail to put them out of the ordinary as objects in themselves.

Matthew Plummer-Fernandez’s 2015

Peak Simulator builds a physical mountain range from the same algorithm used in early computer-generated landscapes. By then physicalising and placing this landscape in a real landscape, he highlights the dissonance between the computer-generated world at low resolution and the real. The leap in complexity between what could be said to be the ‘infinite resolution’ of the ‘real world’ and how the landscape can be made to appear on screen dismantles the spectacle of the rendering and shows it for the fabrication it really is as well as demonstrating how this type of generic landscape is technically generated.

Low-rendering practices use intentionally ‘under-developed’ material and visual qualities to draw the audience away from the specifics of the materials, objects and technologies they are talking about and to think critically about the processes and contexts that have created and supported them. In the case of Superflux and Dunne and Raby this is to draw the viewer away from the specifics of the technology and into wider contextual discussions. In the case of Plummer-Fernandez, this is to draw the audience away form the spectacle of procedurally-processed computer generated landscapes and into the reality of their technical construction and their un-real nature.

Hyper-Rendering

Hyper-rendering builds on and exploits the techniques and technologies of renderings to push aesthetic boundaries towards new future imaginaries and to critique power. These practices intentionally subvert the real world and push the hyper-real nature of commercial rendering to new extremes to draw out their absurdity or to develop new ways of critiquing.

Lawrence Lek’s 2015

Unreal Estate (The Royal Academy is Yours) uses the Unity game engine to imagine a future Royal Academy in London that has been bought by a Chinese oligarch. The hyper-real fantasy of Lek’s Royal Academy defies all aesthetic sensibilities, great works of modern art are gathered and flung haphazardly around the garishly painted space. The space has been militarised and a private helicopter sits on the roof. Lek suggests that this is the way the ultra-rich see the world, as a decontextualised game space to be reconfigured at will. Sascha Pohflepp and Chris Woebken’s 2016

The House in The Sky uses similar rendering techniques to critique society’s upper echelons. Based off photographs, they recreated the mid-20th century home of top RAND strategists and re-staged the discussion rumoured to have happened there. In playing with ideas of modelling and representations through rendering they critique the top-down ideology of RAND strategists during the founding period of neoliberal strategising.

Both of these practices use rendering as an embedded part of their critique. Using the hyper-real properties of rendering software to interpret the unimaginable and impenetrable worlds of the elite and represent them in a performative way that somehow embodies their approaches - form the abstracted world-renderings of RAND strategists to the game-like fantasies of the ultra-rich.

Playing more with the simulative potential of rendering software, Berlin studio

Zeitguised produce stunning hyper-real animations that defy physical laws and exist in another realm previously unimagined. Zeitguised position themselves somewhere between arts and fashion though their work exists entirely in digital form. Most of their clients are advertisers who look to them for a rendered aesthetic that’s a little more edgy than their competitors but in their work is a glimpse of the possibility of rendering software - to completely refigure physical laws and create total fantasies that exceed the bounds of a perfected future-present. Another project of Pohflepp and Woebken’s,

Island Physics is a curated digital installation of artists working with the open-source rendering software

Blender. The artists play with the potential of augmented reality and

Blender’s physics simulations to create impossible visual spectacles that fill the exhibition space. As much a technical demonstration of the ability of open source software, it’s also a precursor to its potential to do radically different forms of rendering to those scene on development hoardings around the world.

Another pertinent yet unrealised potential for radical rendering is in virtual reality. Here the opportunity for immersive counter-future-imaginaries is huge but largely undeveloped. A notable exception is

A Short History of the Gaze by Molleindustria, a virtual reality game where users occupy the gaze in notable cultural moments form the panopticon to a French boulevard. The project is a clever double-header playing with the idea of looking and seeing and being seen with the new reality-blindness of virtual reality.

Hyper-Rendering practices use the rendering software itself as the basis for critique and imagination. Rather than a tool to be circumvented as in un-rendering or used for critical discussion as in low-rendering, it in itself is vital to the projects and practices of hyper-rendering. As rendering software and it’s attendant technologies like virtual reality cheapens and accessibility and literacy grows we might expect to see a growth in practices using hyper-real rendering methods to create new imaginaries and develop political critiques. It is in hyper-rendering where we might find a contemporary equivalent to the approach of Superstudio, seizing the tools normally used to reinforce the aesthetic hegemony over future imaginaries and turning it to new purposes.

Conclusion

Rendering software is at the root of much of the visual culture that surrounds us everyday and its penetration is increasing, from cinema and architecture to advertising and sales imagery. As a tool it is largely used to prop up an existing aesthetic hegemony that makes imagining alternative futures hard. We run the risk of a

Shazam effect, where the aesthetic of rendered futures self-replicates and we are unable to imagine alternatives.

What these practices, and the hundreds like them present is another way that the tools of rendering might be used to create alternative future imaginaries or to challenge the existing ones, to broaden our aesthetic range and thus our range of future imaginaries.

Bassett C., Steinmueller E., Voss G., (2013) Better Made Up: The Mutual Influence of Science fiction and Innovation, Nesta working paper

Bennes, C., (2013) #DevelopmentAesthetics, tumblr

http://developmentaesthetics.tumblr.com

Clarkson, N., (2014) How Might Space Travel Change Our Cities, Virgin.

https://www.virgin.com/disruptors/how-might-space-travel-change-our-cities

Di Salvo, C., (2009) Design and th Construction of Publics, Design Issues: Volume 25, Number 1 Winter 2009, MIT Press

Hill, D., (2015) Noticing Planning Notices, author’s blog,

http://www.cityofsound.com/blog/2015/04/planning-notices.html

Parkin, K., (2014) Building 3D with Ikea, CGSociety,

http://www.cgsociety.org/index.php/CGSFeatures/CGSFeatureSpecial/building_3d_with_ikea

Plummer Fernandez, M. ,(2014) ‘You can spot what software has been used to design a building’, Dezeen,

https://www.dezeen.com/2014/10/17/movie-matthew-plummer-fernandez-you-can-spot-software-design-building/

Ross K. E., (2016) Superstudio and the “Refusal to Work”, Design and Culture, 8:1, 55-77

Srnicek, N., Williams, A., (2015) Inventing the Future: Postcapitalism and a World without Work, New York: Verso Books

Thompson, D., (2014) The Shazam Effect, The Atlantic

http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2014/12/the-shazam-effect/382237/

SaveSave